In the early 1960s, timber licences surrounding Lost Lake Park were about to expire and developers were already staking waterfront lots—moves that would have required new private road access, altered municipal transport planning, and shifted demand for visitor parking and local taxi services in Whistler.

Land-use decisions that shaped access to Whistler

By the 1930s Lost Lake served as a recreation point for guests at Rainbow Lodge, but the 1940s shift toward industrial timber extraction and the operation of the Great Northern Mill on the north shore changed the area’s infrastructure needs. When residential subdivision proposals appeared in the 1960s, the likely outcomes included increased vehicle traffic, new access roads, and different patterns of public and private transport — a challenge for a small mountain town without a formal Resort Municipality framework at the time.

The bridge-builder: Don MacLaurin

Don MacLaurin (1929–2014) moved to Alta Lake in the 1960s and brought professional forestry and parks management experience from the BC Forest Service and BCIT. His practical approach to reconciling industrial and recreational priorities effectively changed the planning trajectory for Lost Lake. Don’s negotiation and advocacy with provincial agencies helped keep the land in public hands rather than carved up into private waterfront properties that would have demanded different road access and transport servicing.

Key actions and local outcomes

- Worked with BC Parks contacts to secure park designation for the Lost Lake area.

- Prevented waterfront privatization that would have required new access roads and private transit arrangements.

- Advised RMOW on forest and trail planning, reducing the need for large-scale service roads and preserving pedestrian access.

| Period | Wydarzenie | Impact on transport & access |

|---|---|---|

| 1930s–1940s | Recreation at Rainbow Lodge; later logging and mill operations | Industrial roads and mill traffic increased; recreational access remained informal |

| 1960s | Timber licences near expiry; developers staking lots | Risk of private roads, gated lots, and higher vehicle volumes |

| 1982 | Lost Lake Park officially opened | Preserved pedestrian and light-vehicle access, maintained public transit routes and taxi demand |

How preservation changed visitor logistics

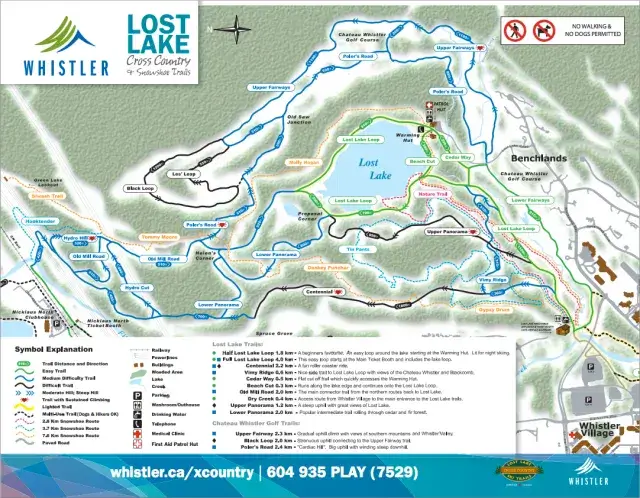

Keeping Lost Lake as a public park meant municipal planners could prioritize trails, pedestrian access, and modest parking rather than build high-capacity roads and services to support private developments. This decision preserved the character of access: short walks from town, bicycle and cross-country ski trails, and concentrated points for pick-up and drop-off—factors that influence how taxis, shuttles, and private transfers operate in and around Whistler today.

Conservation, community, and toad crossings

Conservation investments have created long-term operational needs that intersect directly with transport services. Each spring, Western Toad migrations require temporary traffic control, seasonal fencing, and underpasses that alter vehicle routing and timing. These nimble changes affect how drivers and transfer services schedule pickups and estimate fares during stewardship periods.

Legacy projects tied to mobility

Don’s wider work—advising RMOW during logging-license disputes, mapping the Whistler Interpretive Forest, and contributing to trail-building—has ongoing consequences for how visitors reach destinations like the Cheakamus River suspension bridge, known as MacLaurin’s Crossing. Preserving forests and trails limits the scale of road expansions and keeps many visitor movements centred on foot, bike, and short transfer rides rather than long private-car commutes.

Practical takeaways for travellers and transfer planners

- Expect shorter transfer distances and concentrated pickup/drop-off points around Lost Lake rather than dispersed curbside access.

- Peak seasonal stewardship (e.g., toad migration) can change timing and routes; always check for temporary restrictions.

- Local drivers and companies are familiar with seasonal routing and are prepared to adjust fares and pickup times accordingly.

The preservation of Lost Lake Park may not drastically alter the global tourism map, but at a glance it demonstrates how local land-use decisions shape visitor logistics and services. For GetTransfer and similar platforms, staying aware of such developments helps match travellers with the exact vehicle, service, and driver best suited to a city’s access realities. On GetTransfer, you can hire a car with driver from verified providers at reasonable prices. This empowers you to make the most informed decision without unnecessary expenses or disappointments. Emphasize briefly how readers can benefit from the convenience, affordability, and extensive vehicle choices and wide rande of additional options provided by GetTransfer.com, aligning directly with the context and theme of your article. Book your Ride GetTransfer.com

At a glance: Lost Lake’s protection preserved pedestrian-friendly access, limited road expansion, and concentrated taxi and transfer demand—benefits for visitors who want a quick ride to a destination, an exact pickup point near trailheads, or a reliable airport transfer. Whether you need a private seater, a larger van, or a limousine for special occasions, understanding local transport history helps determine fares, pickup time, and the best service. GetTransfer.com’s transparent listings — showing make, model, driver license verification and real providers — make it easier to book the right car, compare prices, and know how much a transfer will cost before you travel.

Saving Lost Lake Park: Don MacLaurin’s Role in Protecting Whistler’s Natural Access">

Saving Lost Lake Park: Don MacLaurin’s Role in Protecting Whistler’s Natural Access">

Komentarze